Welcome to the world of the globetrotters

You have reached the oldest and probably the most popular travel service in Poland.

Here you will find both experienced globetrotters and people who simply love the idea of travelling.

The service was founded in 1976 as BIT (the Tramping Information Bank), obviously not on the Internet, but at the Almatur student travel office in Krakow. It quickly developed into a major archive, storing information on trips made to all corners of the globe. In 1994 it was renamed TRAVELBIT and in 1997 it made its debut on the Web. Both BIT and Travelbit are the brainchild of Andrzej Urbanik (traveler and physician-radiologist; otherwise known as “Tourbanik”). Currently the website is written and maintained by its founder in collaboration with a number of other travellers and it functions as a community service.

It operates in a non-commercial way – it gathers and makes available information on travelling and serves as a focal point for the travelling community in Poland.

“Trekking” with Travelbit has made travelling easier for thousands of regular joes and josephines while experienced travellers have found a place for themselves here in cyberspace.

OUR DISCUSSION FORUM is especially active and its numerous thematic sections provide extensive sources of information. Our links page is especially valuable in this respect (containing several thousand addresses). Thanks to www.travelbit.pl you can take part in travellers’ meetings all over the country, above all in OSOTT, the Nationwide Meeting of Globetrotters, Tramps and Tourists, which has already assumed cult status. OSOTT is the most prestigious meeting of travellers in Poland and has been organised uninterruptedly since 1985. Individuals can also use our website to advertise their own meetings to the travelling community.

The services provided by www.travelbit.pl are completely free of charge. If you want to cite any materials, all you need to do is give the name of the author (first name, last name, or, if need be, a pseudonym and, if the author has given one, a website or-mail address; copyright regulations must be observed) as well as a link to www.travelbit.pl . Nothing more!

The history of Polish globetrotting makes a passionate tale.

It all began quite impressively.

The first – if he can be called that – Polish globetrotter was Benedykt Polak (Benedictus Polonus) and he was one of the main participants in the biggest ever expedition to Mongolia organised by Europeans in the 13th Century (1245-47). The expedition was a pioneering event of epochal importance in Europeans’ discovery of Asia. The main goal of the expedition was to discourage Mongol attacks on Christian states and convert the khan and his subjects to the faith of Christ. Since Europeans’ knowledge of the Asian interior was sketchy to say the least in those times, one more additional aim of the expedition was to gather information about the lifestyle, beliefs, customs and organisation of the Mongol state.

The great khan refused to co-operate, and, what’s more, demanded that all of Europe’s leaders come to his capital to pay him homage. Despite this setback, the expedition was still a success, since priceless information was gathered for a number of later descriptions of these countries. According to research, three accounts were written. The most extensive, Historia Tartarorum (manuscript in the possession of Yale University), has been credited to Benedykt Polak. One should bear in mind that Benedykt’s expedition took place a quarter of a century before that much better known journey made by the Venetian Marco Polo. Experts also contend that Benedykt’s Historia Tartarorum is a much more credible account than Marco Polo’s Le divisament dou monde (“The Description of the World”, better known as “The Travels of Marco Polo”).

In 2004 (June – September) an expedition from Poland followed in the footsteps of Benedykt Polak, taking the route described by their fellow countryman.

Over the next few centuries Poles travelled throughout the world, although they were not the most prominent or ardent travellers during this period. And when it came to travelling by sea well there’s the infamous saying „the Pole doesn’t know what the sea is when he’s ploughing the land”. And when in the 18th and 19th Centuries other European states embarked on their campaigns of expansion, in particular to Africa and Asia, Poland was erased from the world map, partitioned by Austria, Prussia and Russia. All the more deserving of our respect, therefore, are those Polish travellers who showed great vision and determination in making it to the most distant places in the world.

A great boom in globetrotting, i.e. travelling without the help of a travel agency, occurred after the Second World War. It coincided with major advances in world tourism after the first years of post-war economic reconstruction and the formation of new international links, i.e. in the 1950s. Tourism proved to be the fastest growing branch of the world economy, and for some countries – attractive because of their sea and sun – it provided a veritable boon. Initially the tourist bug benefited Europe, but as Europe and North America grew wealthier, more remote locations began to arouse travellers’ curiosity.

The advent of motoring led to the glory days of hitch-hiking, a mode of travelling that provides even those with very meagre funds with a chance to see the world. Indeed, in the 1960s it became downright fashionable to the thumb a lift. Apart from Europe itself the most popular path taken by hitchhikers led from Europe to India, Nepal and even as far as South-East Asia. This route was traversed by hundreds of hippies in search of narcotics and a different, happier world.

Apart from hitchhiking people made their way to the East, indeed all over the world, by all kinds of vehicles – motorcycles, passenger cars, minibuses, lorries and even London double-decker buses. Sometimes these future conquistadors of the world’s roads were originally found on scrap heaps and restored to life.

The most popular vehicles were the Volkswagen “beetle”, the Volkswagen minibus, known as the “cucumber” and the Citroen 2 CV, popularly called the “duck”.

Round-the-world trips became fashionable at this time.

Globetrotters included a number of Poles in their ranks.

In 1974, Marek Michel travelled around the world on a Polish WSK motorcycle, and in 1977-79 Andrzej Sochacki (a resident of the USA) circumnavigated the globe in a Volkswagen „beetle” (in later years Andrzej made many round-the-world trips by car, motorcycle, train and yacht…).

One journey worthy of note is that made in 1957 by Tony Halik, a traveller who ended up in America after World War II, who drove from Tierra Del Fuego to Alaska in a jeep, a trip which took him 1,536 days to complete. In other words, it took him more than four years to accomplish the feat. He was accompanied by his wife (another traveller) and his son Ozana, who was born en route. The journey was an incredible adventure and was recorded in the film “The 180,000 km adventure”, which was a hit all over the world. The film was an inspiration for another journey – almost 30 years later, Jerzy Adamuszek, a Pole living at the time in Canada, made the trip from Tierra Del Fuego to Alaska in a seven-year old Cadillac going at rally pace and making it into the Guinness Book of Records. He covered the 23,527 km distance in 18 days, 11 hours and 15 minutes.

Roman Turski, another Pole who has lived outside the country since 1945, also made a Trans-American trip in the 1970s. He has spent his entire life on the road (having visited around 150 countries). In many of them he has been accompanied by his Japanese wife.

At a time when globetrotting was regarded as a natural thing to do, if not a way of life, in the Free World, Poland found itself on the less fortunate side of the “Iron Curtain” which divided Europe after the Second World War following the agreement made by the Allies at Yalta. Poland and other Eastern European states were called the Peoples’ Democracies or the Socialist Bloc. They found themselves under the “guardianship” of their Big Neighbour and Brother, i.e. the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Passports became a rationed good and it required great willpower and fortitude to be a globetrotter. Finances also posed a formidable barrier. During those times, the average wage in Poland (known officially as the Peoples’ Republic of Poland – PRL) was approx. $15 a month. What is more, foreign currency could only be taken out of one’s own account and paying into it required documented proof of the origin of the money. Hence only a small cohort of adventurers and daredevils managed to make it to more remote and exotic climes. Most often Poles could only see the world on official trips or on mountaineering or sailing expeditions. However, it should be admitted that of all the peoples living in socialist states, the Poles had the best chances of getting out. Obviously, Poles who lived permanently abroad could travel around the world unhindered.

The Polish globetrotting movement has its roots in different sources.

To begin with, hitchhiking (“auto-stop” in Polish). This way of getting around became very popular in Poland at the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s and stayed so up until the 1980s. You had to buy a special hitchhiking coupon book which identified your name as a hitchhiker. Drivers received coupons every time they gave someone a lift and those who collected the most received rewards. This way of getting from A to B gave you not only a feeling of freedom but also of independence and responsibility. It also served as a “university of life” for many young people. Hitchhiking was so popular that during vacation time the hard shoulders of Polish roads were „choc a block” with Polish young people bearing their signs and waiting for their vehicle.

Another major source of inspiration were excursions, especially mountaineering trips. In the 1960s an expedition organised by a mountaineering club was one of the few means of getting to almost any point in the world. The accomplishments of many of these ambitious outdoor sporting expeditions awakened admiration even beyond Poland. They also had an enormous impact on later, larger expeditions whose simple aim was to discover the world (without any competitive goals). Participants of these expeditions shared their experiences (how to travel on little money, how to overcome red tape…) in slide shows attended by hordes of would-be travellers. These slide shows brought more distant and exotic places closer to Poles.

Sailors, kayakists, scuba divers and members of other clubs also organised trips. Any excuse to “break out” to the world beyond was welcome. A journey made by the Krakow-based „Bystrze” Kayaking club was greeted with much fanfare. In 1979-81 it kayaked all over America from the USA to Peru, exploring ever more difficult rivers until at last they made the first ever crossing of the world’s deepest canyon – the Colca in Peru (which earned them a place in the Guinness Book of Records).

In 1985, one of the members of that expedition, Piotr Chmieliński (at that time a resident of the USA), became the first person in the world to navigate the Amazon from its source to its mouth. He was mentioned in the Guinness Book of Records a second time in 1992 and the New York Times included his feat in its list of the 20 greatest achievements in exploration of the last 100 years.

Despite the fact that foreign travel was problematic, a large number of travel books appeared on the Polish publishing market. Geographical magazines such as “Know the World” and “Continents” also proved a hit. A glimpse of the great wide world was also privately imported into Poland via copies of „National Geographic”, which had by then already become a cult geography magazine.

A number of guidebooks also appeared at this time. However, for the most part they were descriptive publications (geographical, historical and economic in nature) and contained no practical information.

A major role in describing and bringing the outside world closer to Poles was played by Ryszard Kapuscinski, the legendary journalist of both national and global renown and a perfect gifted with a perfect sense of how to relay information, atmosphere and events. He possessed an excellent ability to observe and perceive what was invisible to others. He had a reporter’s gut instinct for finding a story wherever it was taking place. He could be found in places where others feared to tread. He claimed that he only wrote about what he had personally seen and experienced. He often placed his own life and health at risk. This is undoubtedly one of the main reasons for his staggering popularity among his readers.

One amazing phenomenon during this period was “The Six Continents Club”, a television programme devised and presented (beginning in 1968 and lasting for 20 years) by Ryszard Badowski, a journalist, traveller and the first Pole to visit all continents of the globe. Both amateur and professional travellers talked about their adventures on the programme while sitting in the ‘Cafe Under the Globe” conjured up by the programme’s set designers,. It offered viewers a genuine glimpse of the world and also an unusually inspiring one…

One of the Badowski’s guests was Tony Halik, who appeared on the programme after he returned to Poland in 1975. He took his camera with him virtually all over the world and shot more than 300 films.

Soon he and his wife Elzbieta Dzikowska (a journalist and traveller) began to present their own programmes, the most popular of which were “Tam gdzie pieprz rośnie” (“On the Other Side of the World – literally “Where the pepper grows”)” and “Pieprz i wanilia” (“Pepper and Vanilla”).

In 2003 (after his death), the Tony Halik Museum of Travellers was opened in the town of his birth – Torun.

Also worthy of a mention were Bogdan Sienkiewicz’s productions on TVP Gdansk. The first of his series, called “The Flying Dutchman” (first broadcast 1967) was a colourful and attractive show about seafaring topics, and quite a few of its viewers would grew up to be sailors and travellers. Bogdan’s second programme was called “Around the World” and – as was advertised – allowed viewers to “get to know the world without visas or foreign currency”.

Another source of great inspiration for travellers were the films of Stanislaw Szwarc-Bronikowski. He produced well over a hundred on nature, the environment, ethnography, archaeology, geology and religious subjects. The majority of these were accounts of his travels to the wildernesses of continents, in search of unusual phenomena and dying cultures. Just as important were his more educational projects, i.e. travel reports and film journalism.

Leonid Teliga’s solo voyage around the world (1967-69) in his yacht “Opty” made an enormous impression on all aspiring explorers (and not only those interested in water). Teliga joined a select group a dozen or so sailors from five countries who have managed to circumnavigate the globe, and what is interesting is that he achieved this feet entirely on his own without any sponsors.

The second half of the 20th Century is full of amazing challenges undertaken by Polish seafarers, perhaps the most famous being made by Krystyna Chojnowska-Liskiewicz, the first woman in the world to traverse the globe in a yacht singlehandedly.

And Andrzej Urbanczyk (a resident of the USA) made it into the Guinness Book of Records for making solo voyages on all the world’s oceans. He published more than 35 books about his travels. He made his maiden voyage in 1957 when he crossed the Baltic in a wooden raft (a feet which he repeated half a century later in 2007).

Poland’s passport and currency regulations were relaxed at the beginning of the 1970s and it became easier (but still not that easy) to obtain a passport and officially buy a “currency ration” of $130 and later $150. Thus equipped you could then set off for the outside world. It was also “permissible” to open a foreign currency account, into which you could deposit foreign cash, initially with documented proof of its origin, although later even this requirement was rescinded. If, therefore, you had a foreign currency account you could withdraw money from it abroad.

These reforms helped swell the ranks of Poles managing to travel outside the country, and backpackers were among them. They made their way by hitchhiking and all available means of transport, provided the price was within their means. Moreover, during this period Poland got “behind the steering wheel”, i.e. production of the popular Fiat-a 126p, the car for the “masses” was launched, which earned the nickname the “tiny tot”, because of its diminutive size. Poles, i.e. citizens of the People’s Republic, drove around the world in these „tots”. The little Fiats negotiated the highest passes of the Alps, reached the North Cape and their air-cooled engines overheated in Africa. They acquitted themselves grandly in the Middle East and even got as far as India. Some even appeared on the roads of the USA. There were enthusiasts who even organised round-the-world trips in these cars, which, after all, were really designed for the city (engine capacity – 600 cm).

Another option was to travel on Polish merchant vessels, which voyaged to all the most interesting ports around the world. Most of them had passenger cabins and if you had the time and the money you could see the world this way.

For those in a hurry, Eastern European airlines (Aeroflot – USSR, Interflug – the German Democratic Republic, CSA – Czechoslovakia, Balkan – Bulgaria, Tarom – Romania, Malew – Hungary, Cubana – Cuba, MIAT – Mongolia and of course LOT – Poland) offered flights at prices that were often many times lower than flights on the same routes provided by airlines from countries with “healthy” economies.

In 1973 the Asia and Pacific Museum opened in Warsaw, founded by the traveller, diplomat and collector Andrzej Wawrzyniak, who donated as a gift to the State Treasury his collection of ethnographic items and works of art from the islands of Indonesia collected over the course of more than 30 years spent in Asia. The collection not only marked the beginning of the museum itself but also served as a valuable a source of information and a platform for exchanging travelling experiences.

Although the regulations had been considerably relaxed, travelling abroad remained a difficult undertaking due to the logistics, i.e. the troublesome red tape involved in getting a passport. You had to apply for a passport every time you went abroad – submitting the form and actually obtaining the desired document often meant standing in a queue for several days; obviously you didn’t queue non-stop, rather shifts were organised and enforced by special queuing committees.

Even after all this effort, however, you were not always guaranteed success. It was the authorities that issued passports and it was solely “at their discretion” whether you would get the chance to travel around the world. Refusals were not uncommon, because the authorities knew what was best for their citizens …

There were also problems when it came to obtaining a visa (they were required for all countries with the exception of Eastern Europe) and obviously you also had to have the necessary funds for travel. It is important to note that a passport was only issued for each specific trip and you had to surrender it to the passport office within seven days of your return.

Undaunted by these obstacles, however, more and more individual travellers were now making trips outside Poland. A major turning point in student travel occurred at the beginning of the 1970s when students were allowed to organise what were called “environmental trips”.

The assumption was as follows. A group of students got together (a minimum of 10 people), prepared a programme for a trip together with a preliminary cost estimate and submitted these documents to an Almatur tourist office.

At the beginning of each year, a kind of competition was organised to choose the most interesting ideas and allocate them foreign currency rations. The maximum sum available was originally $130 per head and later this was increased to $150, which each participant had to buy. The great attraction of these competitions lay in the fact that they offered an exchange rate of PLN 20 for the US dollar, whereas the black market rate was over PLN 100!!! Almatur also arranged for passports (sometimes they also helped out with visas), which saved travellers a great deal of time and effort. In this way, Poles could travel around the world relatively cheaply (at any rate much more cheaply than with a travel agency). The most important person in the “environmental group” was the driver, who was responsible for the programme, logistics and keeping the cash, and was also often the group’s “strong arm”. The success of the venture depended to a very great extent on his inventiveness and resourcefulness. The group could travel where and how it wanted (obviously within the limits of their programme, budget and most often the visas they possessed). They offered a unique feeling of freedom and independence, especially for Polish students during those years…

Originally, most of these trips headed for countries in the Middle East because they were colourful and exotic, full of ancient monuments, culturally different, relatively easy to get to, and fairly cheap to get by in. At that time, getting to India posed a great challenge. People got there using cheap transport via the USSR, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Lorries offered another mode of travel. They served not only as a means of transport, but also functioned as a hotel and a place for storing gear and, most importantly, food supplies. In other words, you coped in a variety of ways, just as long as you achieved your desired goal.

1976 was a landmark year for “environmental trips”. Organising these trips (or expeditions) became very popular and Almatur received well over a hundred suggestions in its competition that year. Almatur’s Krakow branch had to set up a special department for organising environmental trips, which Andrzej Urbanik and Marek Sawiuk (two students – of medicine and archaeology, respectively) nicknamed the “tramping department”. The moniker proved so popular that it became obligatory to call all environmental trips by this name and from that time on the Polish globetrotter community, i.e. „free” travel – as opposed to organised excursions – began to be known as the “tramping” community. In 1976, Andrzej Urbanik, the head of the tramping department in Almatur’s Krakow branch founded BIT, otherwise known as the Tramping Information Bank (since 1994 it has been operating as Travelbit). This somewhat grandiloquent name simply referred to the ringbinder in which Andrzej kept reports on journeys made by himself and friends. These reports, which mainly consisted of practical information – the what, where, how and how much of travelling – filled up the binder quickly and it became the most priceless in, well perhaps not the whole world, but certainly in Krakow.

These contacts with the outside world bore fruit in a wholly unexpected discovery. For it turned out that besides the cognitive value of discovering new places you could also make just a “little” cash by exploiting differences in prices between products in Poland and other countries and also the fact that more and more things were in short supply in Poland – living standards had declined as the economic crisis had worsened. Hence the majority of trader-globetrotters tried to make money on these trips to finance later, often more costly and adventurous trips.

These “business” opportunities allowed Polish globetrotters to make greater use of air travel. Although airline tickets were admittedly expensive, Polish traders could “make up for” these overheads with their goods, hence air travel (obviously via Eastern European airlines) became an attractive option. It also allowed Poles to broaden their horizons to include the Middle East, Japan, Africa and even America.

The Krakow travelling community also devised its own original system for seeing the world – they discovered a way of buying tickets on Soviet cruise ships on the Mediterranean at very low prices. You could interrupt your voyage at any port of your choice, travel by land and later return to the ship at another port. One interesting option this system offered was that you could pay a one-day visit to any port without the need for a visa (You surrendered your passport for deposit and went on land with a “token”). In this way Poles organised journeys to Japan, combining the Trans-Siberian railway with a ferry ride on the Nahodka (Validvostok) – Jokohama route.

In 1979 the Krakow branch of Almatur helped publish a brochure entitled “The Tramper’s Handbook” authored by Andrzej Urbanik. The writer was one of the principal organisers of the tramping movement in the Krakow community as well as the head of Almatur’s tramping department. The brochure described the author’s experiences on numerous journeys to different parts of the world. It was the first publication of its kind in Poland and became a kind of “globetrotter’s bible” read diligently by future “discoverers of the world”.

At the beginning of the 1980s the Polish tramping movement evolved on a much bigger scale. Moreover, it is interesting to note it was created more by people than organisations. The Almatur student travel office was treated solely as a means of obtaining cheap currency and transport discounts as well as a channel through which passports, and often also visas, could be acquired more easily.

The mushrooming of the globetrotting movement was checked by the introduction of Martial Law on 13 December 1981. Overnight, all borders were closed and tourist trips suspended … and all the progress that had been made up till that point appeared to have been lost. However, even in such circumstances travellers were still able to do a lot to realise their dreams. By the 1982 vacation period, tramping trips were already setting off from Krakow for … Mongolia. A journey to this previously overlooked country (part of the Socialist Bloc) turned out to be a great adventure and a great test of one’s organisational abilities.

Martial Law was lifted on 22 July 1983 and the tramping movement was revived once more. Polish globetrotters at that time had to have extensive and specialist knowledge since for the most part they were forced to rely on their own ingenuity and resourcefulness, especially group drivers – they had to function as airline check in desks, ethnographers, geographers, historians, guides and often psychologists. And all of this was done against the backdrop of a fast changing world.

Slide-show meetings organised by trip participants became an inseparable feature of the tramping community. These were enormously popular because they allowed people to gain more up-to-date information direct from the source. In this way local or regional tramping groups were created.

Another major turning point in the history of tramping occurred in 1985. The earlier mentioned Andrzej Urbanik came up with the idea of organising national meetings for travellers.

Andrzej christened the new network OSOTT. The first gathering took place in November 1985 with 50 trampers from all over Poland taking part. In the next few years more and more travellers attended OSOTT gatherings and this led to the formation of a national tramping lobby, which played a major role in promoting the globetrotter movement in Poland.

In 1986, the illustrated tourist magazine Światowid (“View of the World”) discussed the emergence of the tramping lobby. The upshot of this encounter was the creation of two regular columns in the monthly . In the first, “The Globetrotter’s Handbook”, Andrzej Urbanik offered previously inaccessible practical information on the most exotic corners of the globe. In the second column “The Globetrotters Club” – Liliana Olchowik described recently completed tramping journeys based on interviews with participants, which showed that in spite of all the obstacles Poles could travel all over the world on a shoestring budget.

These pioneering publications in Poland were invaluable to the tramping movement. They enabled thousands of would-be travellers to join the tramping trail and turn their private dreams into reality.

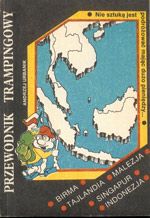

The first Polish globetrotter’s guide appeared in Polish bookshops in 1987. It described countries in South-East Asia, i.e. an increasingly popular region of the world for Polish globetrotters. It was called “A Tramping Guide – Burma, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia” and was written by Andrzej Urbanik.

Its popularity surpassed the wildest expectations of its publisher who had doubted whether such a book was even necessary and thus initially published only a limited edition (although reprints were later made). The guide soon disappeared from the shelves of bookshops and it fetched a black market price of around 10,000 zloty (as compared with its official price of 600 zloty in the bookstores). Several generations of travellers were to make their way around this beautiful part of the world armed with Urbanik’s guidebook.

Poland then went through the great political, social and economic changes of 1989. Poles’ determination led to the downfall of the communist regime in their country, which in turn triggered the collapse of the communist system in Eastern Europe as a whole. Freedom returned. Most importantly the outside world was opened up to Poles. Passport restrictions were done away with and soon afterwards anyone could have their own passport in his or her drawer at home. What is more, other countries began to relax their own visa requirements for Poles. One effect of the “Balcerowicz Plan” was to bring the official exchange rate against the dollar (and other currencies) in line with reality, as a result of which the value of the USD declined in 1990 (the average salary in Poland grew in 12 months from around $20 to $100). Soon, Poles could buy and sell currency in exchange rate offices which sprouted up everywhere.

These events also had more specific implications. Disparities in the cost of living between Poland and the rest of the world began to diminish. The relative decline in the value of the American dollar meant that the financial burden facing Polish travellers shifted from the cost of living in the target country to the cost of transport itself. Prices between Eastern and Western airlines evened out and as a consequence Eastern European airlines declined in importance as the most important mode of transport for Polish globetrotters.

A number of guide books now appeared on the shelves, which were of greatly varying quality (often their authors had not even been to the places they described and instead had simply transcribed information from foreign publications and encyclopaedias). On the other hand, they contained more and more practical information. They were targeted at people who were for the most part planning to go to countries which no longer required Poles to have visas. Globetrotter magazines also began to appear in 1989-92. The first was Globtroter followed later by Travel. They were published by the Institute of Tourism in Warsaw.

Shortly, however, the majority of decent publishers in Poland began to turn out an increasing supply of guidebooks, mainly translated from foreign languages. In 1992 the Pascal publishing house was founded. It started to publish the world’s most popular guides: Let’s Go, Rough Guide and Lonely Planet. The company rapidly emerged as the market leader in the field. In 1999 Bezdroża appeared on the market. It specialised in guidebooks on the places of most interest to genuine globetrotting connoisseurs (most of the authors being Polish globetrotters themselves).

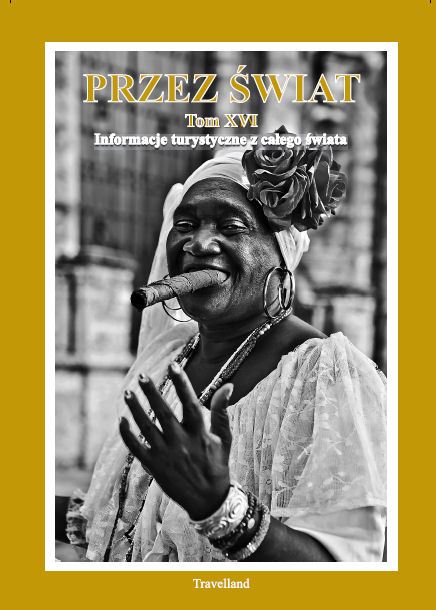

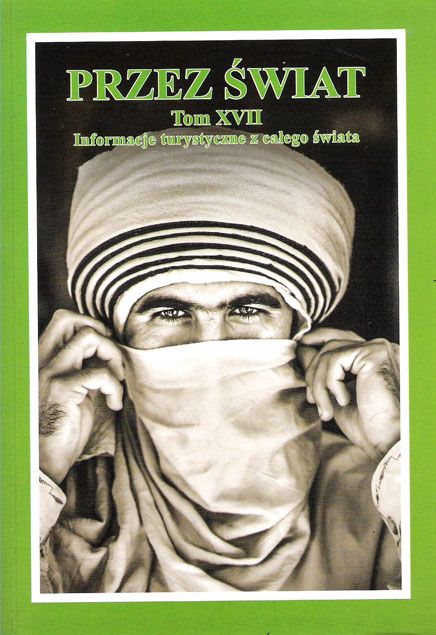

A highly unusual series began to see the light of day in 1996. Each successive volume of the series (they are published every year) contains highly detailed and informative accounts of journeys made to interesting corners of the globe, both near and far. The authors are Polish globetrotters keen to share their experiences with the reader. The series is called “Across the World – Tourist Information From All Over the World” the editor and brainchild behind which is Andrzej Urbanik. The success of these tomes has exceeded the expectations of both Mr Urbanik and the publishers. They have served as trusty companions on journeys to even the most exotic parts.

However, the biggest commotion (in the positive meaning of this term) in the travelling world was probably stirred up by the 1992 publication of a book with the curious title “Let the Whole World Think You’re Mad, i.e. Getting to India on 30 Dollars”, in which the author (Edi Pyrek) described his insane overland escapade to India on a budget of just $30! This tale was written in simple and colourful language that appealed to the imagination of people who hitherto would never before have even contemplated going to such exotic locations. The book encouraged many a travelling rookie to set off on the globetrotting trail.

In the second half of the 1990s Polish travel websites began to appear on the net. The one of the first (set up in 1997) was www.travelbit.pl.

New travel magazines also made their debut, although some eventually folded, unable to survive on a difficult market. The Polish edition of the world’s most popular travel-geographical magazine – National Geographic – also came onto the newsstands at this time.

Editorial teams began to organise various competitions for “Traveller of the Year” or “Travelling Feat of the Year”. The first and most important of these accolades were the „Kolosy” , i.e. special awards for the best Polish accomplishments in the world of travel and exploration (conceived by Janusz Janowski). The awards, figurines shaped like Easter Island statues, have been handed out every year since. Most importantly, the ”Kolos” is an entirely honorary award!

This brought to a close a certain chapter in the history of Polish tramping and the Polish travel community. Henceforth it began to function on principles similar to those in the “civilised” world. The unique phenomenon of Polish travel, i.e. the emergence and growth of a globetrotting community in a country in which the authorities had only reluctantly allowed its citizens access to the outside world, is described in a handbook entitled “Tramping Journeys”, written by the head of the Institute of Tourism in Warsaw, Krzysztof Łopaciński (himself a traveller and one of the pioneers of the movement).

In 2002 a special book was published entitled “Discovering the World – Poles on Six Continents, i.e. the Feats of Polish Travellers” (author – Ryszard Badowski). By the time it appeared on the market Polish globetrotters were already travelling around the world at ease (since 2004 as members of the European Union) and a small number of them remembered the difficult routes taken by Polish globetrotters in discovering and exploring the world.

Historia „polskiego” poznawania świata zaczyna się całkiem efektownie. Pierwszy – jeżeli można go tak nazwać – polski globtroter był jednym z głównych uczestników…

Historia „polskiego” poznawania świata zaczyna się całkiem efektownie. Pierwszy – jeżeli można go tak nazwać – polski globtroter był jednym z głównych uczestników…